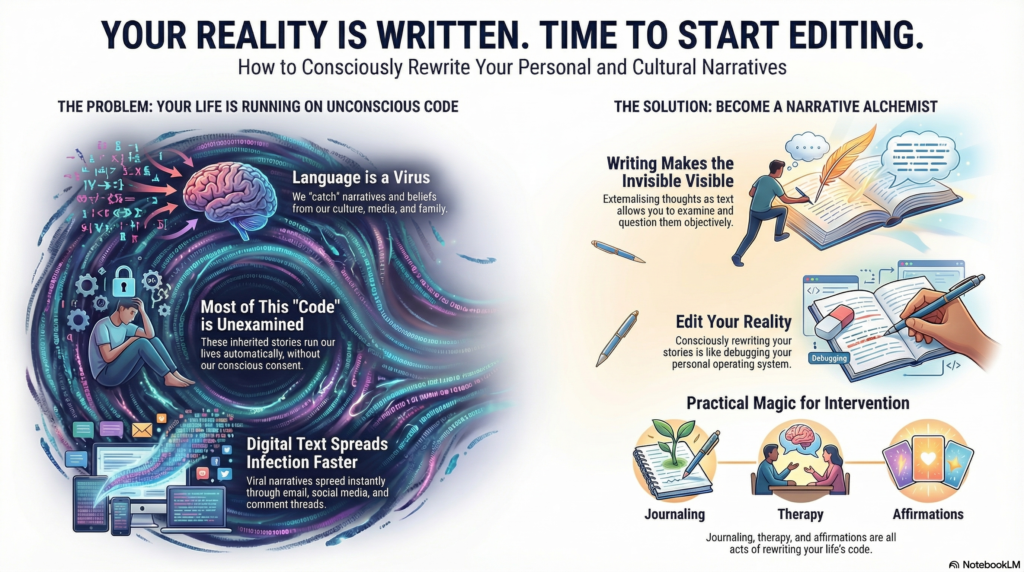

Where Ideas Go to Live

David Allen, the productivity guru behind Getting Things Done, once observed: “Your mind is for having ideas, not holding them.” It’s one of those statements that sounds simple until you actually sit with it. If your mind isn’t meant to hold ideas, then where exactly are they supposed to go?

The answer might seem obvious at first. We externalize our thoughts into notebooks, apps, documents, voice memos. We offload our mental RAM into trusted systems so our brains can focus on what they do best: making connections, generating insights, creating new possibilities. But there’s something more fundamental happening here, something that most of us have stopped noticing because we’re swimming in it.

We live in a world of text.

Not metaphorically. Not as a cute turn of phrase. Literally. The infrastructure of modern reality, the actual substrate through which ideas persist and propagate and gain power, is overwhelmingly textual. And once you see this, really see it, everything about how change works starts to look different.

The Textual Layer of Reality

Look around at the external world right now, not the physical objects but the informational landscape you navigate daily. What is it made of? Social media feeds. Email threads. Slack channels. Policy documents. Meeting notes. Google Docs. Text messages. Direct messages. Comment threads. Reddit posts. Substack essays. LinkedIn updates. The list in your notes app. Your journal. The running commentary in your head that you’ve already half-written as if preparing to type it out.

The external world is increasingly made of written narratives rather than oral tradition or pure, unmediated experience. We’ve undergone a profound shift in how human culture operates, and most of us haven’t fully registered what it means.

For most of human history, culture was transmitted orally. Stories were told around fires, wisdom was passed from elder to apprentice through spoken word, and most of what you knew came through direct experience or conversation. Writing existed, but it was specialized, reserved for the important, the official, the ceremonial.

Now we live in text the way fish live in water. Our “external mind,” the collective space where thoughts go to persist and compound and interact with other thoughts, is predominantly textual. The stories running in the background of culture, of organizations, of individual lives, they don’t primarily exist in speeches or songs anymore. They exist in documents. In threads. In the aggregated text that forms the informational environment we swim through every day.

Text has become our extended cognitive architecture. It’s where ideas go to live.

The Spell That Makes Thought Real

Here’s what makes text different from thought: once you write something down, it feels more real. More solid. More authoritative.

A passing thought is ephemeral. It arises, it fades, it might come back, it might not. But the moment you write that thought down, something shifts. It gains weight. It becomes a thing that exists outside your skull, a thing that can be returned to, shared, built upon, argued with.

Text is the spell that makes thought real and transmissible.

Think about this in practical terms. You can have the same anxious thought loop running through your head for weeks, maybe months. It circles and circles, never quite resolving. But the moment you write it out, the moment you journal it or type it into a document, suddenly you can see it. You can examine it. You can ask whether it’s actually true. The act of textualization makes the invisible visible.

And once it’s visible, it becomes editable.

This is why writing is not just recording. Writing is reality-making. When you put words on a page or a screen, you’re not simply capturing what already exists in your head. You’re creating a new object in the world, one that has persistence (it doesn’t fade like thoughts do), transmissibility (it can travel beyond your individual consciousness), and authority (once written, it carries a weight that pure thought rarely achieves).

If you’ve ever kept a journal, you know this intuitively. The act of writing something down changes it. The thought you had in your head and the sentence you write are related but not identical. The sentence is sharper, or messier, or more precise, or more confused than the thought was. And once it’s written, once it’s text, it has a life of its own.

This aligns perfectly with the framework I call “stories are code.” If text is where ideas gain persistence and power, if text is literally the medium through which thought becomes transmissible reality, then text is functional. It does things. It runs. It shapes what happens next.

Text is the code. Writing is programming. And if you’re not writing consciously, then the default scripts are running on autopilot.

The Implications Cascade

Once you accept that we live in a world of text, that the substrate of modern reality is textual, the implications start cascading outward.

Our Reality Is Textual

The stories that run your life aren’t abstract psychological constructs floating in some mental ether. They exist as text. Maybe they’re in your journal. Maybe they’re in the emails you send. Maybe they’re in the way you’ve phrased your LinkedIn bio or the words you use when you introduce yourself at a party (words you’ve repeated so often they’ve become internalized script). Maybe they’re in the policy documents at your workplace, the employee handbook that defines what’s possible and what’s not.

Your limiting beliefs? They’re not just “in your head.” They’re in the text. They’re in the way you describe yourself to others, in the stories you write about your past, in the narratives you’ve constructed to explain why things are the way they are. They’re in the email you drafted but didn’t send, in the journal entry from three years ago that you still remember, in the comment thread where you defended a position that has since calcified into identity.

Culture operates this way too. Organizational culture isn’t primarily about values stated in a mission statement (though those matter). It’s about the accumulated text: the email chains, the Slack messages, the meeting notes, the way people write about what happened and what it meant. The story of your company, your community, your family exists in text. It’s written, rewritten, and reinforced through the documents that persist and circulate.

If you want to understand what’s actually running in the background of any system, human or organizational, look at the text. Read the emails. Read the journals. Read the repeated phrases, the stories that get told over and over. That’s where the actual code lives.

Change Requires Textual Intervention

Here’s where this gets practical for anyone interested in transformation, in narrative alchemy, in what I sometimes call “debugging reality.”

If the stories that shape your life exist primarily as text, then changing those stories requires intervening at the textual level. You can’t just “think differently.” You have to write differently. You have to literally rewrite the code.

This is not the same as positive thinking or affirmations, though those can be part of it. This is deeper. This is recognizing that the story of who you are and what’s possible for you exists in written form, whether you’ve formalized it or not. It exists in how you’ve narrated your past in therapy, in your journal, in conversations with friends that you then replay in your head as if reading from a script.

When you engage in narrative alchemy, you’re not just changing how someone thinks. You’re literally rewriting the code of their reality as it exists in written form. You’re editing the text.

Journaling works because it externalizes the invisible. It takes the thought loops and makes them visible on the page, where they can be examined, questioned, revised. Affirmations work (when they work) because they’re inserting new text into the system, running different code, seeing what happens when you repeatedly write and speak a different story.

Therapy often works through storytelling, through the gradual rewriting of the narrative of your life. You come in with one version of the story. Through conversation (which is oral but often becomes written, in notes, in journaling, in the way you rehearse what you’ll say next session), the story shifts. Details get reinterpreted. The plot changes. The meaning evolves. And as the story changes, so does the reality it describes.

This is textual intervention. This is editing the code.

The Invisible Made Visible and Editable

There’s a reason why every wisdom tradition, every therapeutic modality, every serious practice of self-transformation involves some form of writing. Because writing makes the unconscious visible.

The thought you can’t quite articulate, the feeling that’s too big or too tangled to grasp, the pattern you keep repeating without understanding why—once you write it down, once you turn it into text, it becomes an object you can work with. You can see it. You can move it around. You can ask questions of it. You can edit it.

This is why journaling is so transformative. Not because writing is magic in some vague, mystical sense (though there is that), but because the act of textualization creates the conditions for change. The moment something is written, it’s no longer just happening to you. It’s something you can examine, something you can choose to keep or revise or delete entirely.

Text makes the invisible visible. And once visible, it becomes editable.

This is the territory that narrative alchemists work in. Not the realm of pure thought, not the realm of emotion or sensation, but the textual layer of reality. The layer where stories persist, where they gain authority, where they can be debugged and rewritten.

Language Is a Virus (And You’re Already Infected)

William S. Burroughs had a phrase that haunts anyone who takes language seriously: “Language is a virus from outer space.”

He wasn’t being metaphorical. Or rather, the metaphor was so precise it stopped being metaphor and became diagnosis. Language operates like a virus. It replicates. It spreads from host to host. It colonizes consciousness. And most crucially: you didn’t write most of the code that’s currently running you.

If we live in a world of text, and text is functional code that shapes reality, then Burroughs is pointing to something we need to reckon with: you catch narratives the way you catch a cold. They install themselves. They run in the background. They replicate and spread, often without your conscious participation or consent.

Think about the stories you tell about yourself. How many of them did you actually author? How many were handed to you by parents, teachers, culture, trauma, offhand comments that stuck, narratives absorbed from media or religion or the ambient ideology of your time and place? How many limiting beliefs are running in your system right now that you never consciously chose to install?

The virus metaphor cuts deeper than just “language influences us.” It suggests that language has agency, that narratives want to reproduce themselves, that stories spread because they’re good at spreading, not necessarily because they’re true or useful or healthy.

You know this if you’ve ever tried to talk someone out of a limiting belief. The belief defends itself. It has antibodies. It generates counter-arguments. It finds evidence for its own validity. It recruits other beliefs to support it. The narrative doesn’t just sit there passively waiting to be edited—it fights back, because that’s what successful viruses do. They resist deletion.

This is why simply “knowing better” doesn’t work. You can intellectually understand that a story about yourself is false, outdated, or self-sabotaging, and still find yourself running that exact code when it matters. The virus is deeper than conscious thought. It’s in the text, in the repeated phrases, in the muscle memory of how you narrate your experience.

The Textual Ecosystem Is Already Infected

Here’s what makes this particularly urgent in a world of text: the replication mechanisms are faster and more pervasive than ever before.

Oral culture had natural limits on viral spread. A story could only go as far as someone could travel and tell it. But textual culture? Text replicates at the speed of copy-paste. A limiting narrative can spread through an organization in a single email chain. A cultural story can go viral (we even use that word now) across millions of minds in hours. The infectious narratives that might have taken generations to spread now propagate in real time.

And most of it happens unconsciously. You read something, it sounds true or compelling or emotionally resonant, and you absorb it. You don’t critically examine it. You don’t check the source code. You just… install it. And then you repeat it. You write it in your own words. You share it. You become a vector.

Social media is a particularly efficient transmission mechanism. The most infectious narratives aren’t necessarily the most true or useful—they’re the ones optimized for replication. They’re emotionally charged, identity-confirming, outrage-inducing, tribal-signaling. They spread because they’re good at spreading.

And every time you engage with that text, every time you quote-tweet or comment or write your own version of the narrative, you’re propagating the virus. You’re not just consuming text, you’re replicating it, mutating it, passing it on.

Narrative Alchemy as Antivirus

This is where narrative alchemy stops being a nice metaphor and becomes urgent practical work.

If language is a virus and we live in a world of text, then being unconscious about what you write and what you consume isn’t just passive—it’s dangerous. You’re leaving yourself open to infection. Every unexamined narrative is a potential vector. Every story you tell without questioning its source code is a virus you’re allowing to replicate in your system.

Narrative alchemy, in this context, is antivirus work. It’s the practice of:

- Identifying the infectious narratives running in your system

- Tracing their origin (where did you catch this story?)

- Examining their effects (what does this code actually do when it runs?)

- Quarantining the malicious ones

- Writing immunizing code to prevent reinfection

When you journal with awareness, you’re not just externalizing thoughts—you’re running diagnostics. You’re looking at what code is running, where it came from, whether it’s serving you or sabotaging you. You’re identifying the viruses.

When you consciously rewrite a limiting belief, you’re not just “thinking positive”—you’re patching a vulnerability. You’re removing malicious code and replacing it with something you actually chose to install.

When you refuse to repeat a cultural narrative that doesn’t serve you, when you stop participating in the textual transmission of a story you don’t believe in, you’re breaking the chain of infection. You’re being a firewall instead of a vector.

The stakes are real. Because in a world of text, the narratives that dominate aren’t necessarily the truest or most life-giving—they’re the most infectious. And if you’re not deliberately choosing what code you run, then you’re running whatever happened to infect you.

Burroughs understood this. Language is a virus. But here’s what he also understood: once you see it, once you recognize the infection for what it is, you can start to develop immunity. You can start writing consciously. You can start treating text not as neutral information but as active code that needs to be examined, debugged, and sometimes deleted entirely.

That’s not paranoia. That’s literacy in a textual world.

For Those Who Believe Words Are Magic

If you’re someone who already understands that words have power, that language shapes reality, that stories are not just descriptions of the world but active forces in creating it, then this matters even more.

You’re a narrative alchemist. A change magician. Someone who works with the technology of transformation. You know that words are magic. You’ve experienced it. You’ve seen how the right phrase at the right time can shift everything, how a reframed story can open possibilities that seemed impossible moments before.

But here’s what happens when you recognize that we live in a world of text: you start to see where the real magic is happening.

The spells are already being cast. The code is already running. Every email you send, every journal entry you write, every social media post, every repeated phrase, every document you create or read or share—all of it is magic. All of it is code. All of it is shaping what comes next.

The question is not whether you’re casting spells. You are. The question is whether you’re doing it consciously or letting the default scripts run on autopilot.

Most people don’t realize they’re living inside unexamined text. They’re running code they didn’t write, repeating narratives they inherited, operating from scripts that were installed by accident or absorbed from culture or written in moments of pain and never updated. The text is running them, rather than the other way around.

But once you see it, once you understand that we live in a textual world and that text is functional, is operational, is code—then you can start writing consciously. You can start debugging. You can start treating your journal not as a diary but as a development environment. You can start treating the stories you tell about yourself not as fixed truth but as editable drafts.

This is what it means to work at the textual layer of reality. This is the foundation of narrative alchemy.

The Foundation Stone

We live in a world of text. That’s not a problem to be solved. It’s the ground we stand on. It’s the medium through which ideas persist and propagate and become real. It’s the layer of reality where transformation actually happens, where stories can be debugged and rewritten, where the code that’s running your life can be examined and edited.

This is foundational. Everything else I’ll write about narrative alchemy, about treating stories as code, about the technology of transformation—all of it rests on this one recognition: the world you navigate is textual, and text is functional.

Once you see that we live in a world of text, you can’t unsee it. And that’s when the real work begins.

You start paying attention to what you write. You start noticing the stories that repeat. You start asking what code is running in the background of your life, and whether it’s producing the results you actually want. You start treating writing not as expression but as intervention, as the primary means through which reality can be debugged and rewritten.

This is where narrative alchemy lives. In the gap between the story as it’s currently written and the story as it could be. In the recognition that text is not passive description but active spell-casting. In the understanding that if you’re going to live in a world of text anyway, you might as well learn to write it consciously.

More to come. This is just the foundation stone.

But foundations matter. They’re what everything else is built on. And now we have one.