I spent twenty years in corporate learning and development watching people master outcome frameworks while their actual lives drifted sideways. They could build project plans with military precision, cascade objectives down organisational charts, and define KPIs that would make a statistician weep with joy. Then they’d leave the office and scroll through their phones on autopilot, accepting whatever the algorithm fed them next, living lives that were happening to them rather than through them.

The paradox gnawed at me: infinite choice had somehow produced a culture of drift.

We live in an age where you can customise your coffee order with seventeen variables but can’t articulate where you want your life to be in five years. We swipe through potential partners like we’re sorting mail. We let Netflix auto-play the next episode because making a decision about what to watch next feels like work. We follow the path of least resistance until we look up one day and realise we’re somewhere we never consciously chose to be.

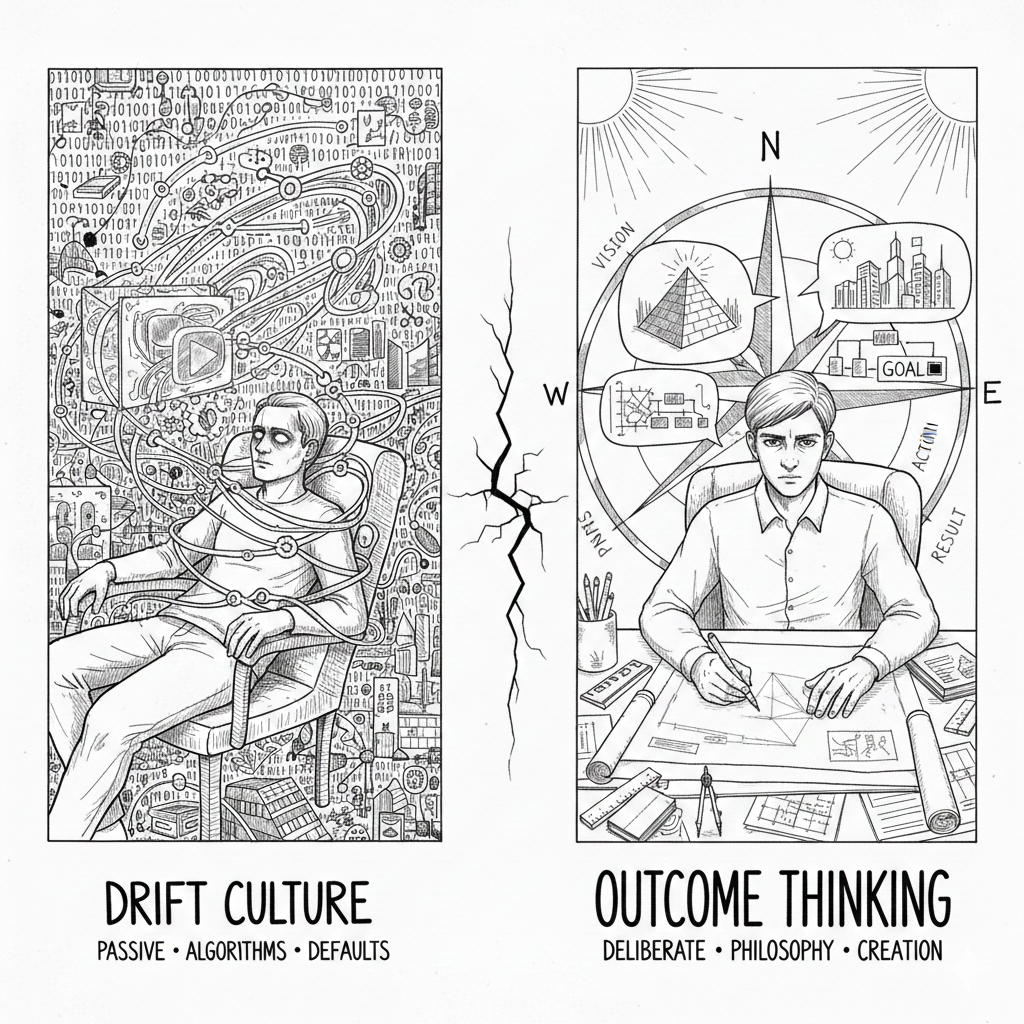

This is drift culture. It’s the passive acceptance of algorithmic feeds, default paths, and cultural currents. It’s living in reactive mode, responding to inputs rather than generating outputs. It’s the spiritual equivalent of being a leaf in a stream, mistaking movement for progress.

But there’s another way.

Outcome thinking, properly understood, isn’t another corporate productivity hack. It’s not about quarterly objectives or SMART goals or any of that tactical machinery. It’s something older and more fundamental: the practice of consciously choosing a destination before you select a method. It’s asking “where am I actually going?” before you start walking. It’s treating your attention, your time, and your life force as something too precious to spend on unconsidered defaults.

This is philosophy as practice.

In an age of manufactured distraction, where entire industries profit from keeping you in drift mode, outcome thinking offers a framework for reclaiming agency over the direction of your life. Not control over every detail. Not rigid plans immune to chaos. Just direction. Intention. And the conscious choice to steer rather than float.

The question isn’t whether you’re moving. You’re always moving. Time ensures that.

The question is: are you drifting, or have you chosen a heading?

The Architecture of Drift

The systems we interact with daily aren’t neutral. They’re engineered with precision to keep us in a specific state: perpetually reactive, endlessly consuming, never quite satisfied enough to stop.

Consider the feed. Not a feed, but the concept itself, now so ubiquitous we barely notice it. The feed replaced the homepage. It replaced the bookmark. It replaced the idea that you might go somewhere specific on purpose. Instead, content comes to you in an infinite vertical scroll, algorithmically selected to keep you engaged for one more swipe, one more minute, one more hit of dopamine.

The feed is architecture for drift.

I remember when the internet had destinations. You typed in a URL because you wanted something specific. You went to a forum to discuss a particular topic. You visited a blog because you valued that person’s thinking. The web was a library you navigated with intention.

Now it’s a stream you float down, and the current is controlled by engagement metrics.

The brilliance of this design, from a business perspective, is that it eliminates the friction of decision-making. You don’t have to choose what to read next. You don’t have to wonder what to watch. The algorithm has already decided, based on what kept people like you scrolling yesterday. You’re not making choices. You’re accepting suggestions optimised for a goal you never consented to: maximum time on platform.

This is passive consumption as the path of least resistance, and resistance has been carefully engineered out of the experience.

The deeper trick is the illusion of choice. You can choose between thousands of shows on Netflix, millions of posts on Instagram, infinite variations of the same arguments on Twitter. The abundance feels like freedom. But all roads lead to the same place: you, in front of a screen, generating data, seeing ads, not doing the thing you said you wanted to do with your life.

The platforms call this “discovery.” But discovery implies agency, exploration, the joy of finding something you were seeking. This is different. This is being carried along by a current designed to keep you in the water.

What makes drift culture particularly insidious is that it masquerades as relaxation, as entertainment, as staying connected. And sometimes it is those things. But mostly it’s the gradual outsourcing of your attention to systems that profit when you stop steering.

Drift is a form of spiritual entropy. It’s what happens when you stop applying energy to direction and let the default flows carry you. And in a system designed to monetise your attention, the default flows don’t lead anywhere you actually want to go.

They lead in circles.

The feed refreshes. The queue auto-plays. The recommendations multiply. You keep moving, keep consuming, keep engaging. But you’re not going anywhere. You’re treading water in a pool designed to keep you from noticing you’re not swimming toward shore.

This is the invisible architecture that shapes our days. Not through force, but through friction reduction. Not through commands, but through suggestions. Not through restricting your choices, but through making the choice to drift easier than the choice to steer.

And after enough years of this, something shifts. You forget that steering was ever an option.

The Hidden Cost of Directionless Living

The bill for drift culture doesn’t arrive all at once. It accumulates quietly, like interest on a debt you didn’t know you were taking on.

Start with decision fatigue. You wake up and your phone offers you forty-seven notifications. Your streaming service wants you to choose between thousands of options. Your inbox demands responses. Your social feeds present endless micro-decisions: like or scroll, engage or ignore, share or move on.

But here’s the trap: none of these choices actually matter.

They’re decisions about consumption, not direction. They’re reactions to inputs, not expressions of intention. You’re spending your finite decision-making capacity on an infinite stream of trivial selections while the actual question, “where am I going with my life?”, never even gets asked.

I’ve watched this play out in my corporate years with brutal clarity. Executives would spend three hours debating the colour scheme for a presentation slide, then accept a career trajectory by default because it was the next logical step on the org chart. The small decisions got all the attention. The big ones happened by momentum.

This is how you end up with a life built entirely from unconsidered defaults.

You take the job because it was offered. You stay in the city because that’s where the job is. You date according to the patterns the apps present. You consume the content the algorithm serves. You adopt the opinions that dominate your feed. You buy the products that sponsored your favourite creator. Each individual choice seems reasonable, even inevitable. But you never stopped to ask: is this the direction I actually want to go?

The defaults accumulate into an identity.

And here’s what makes this particularly dangerous in our current moment: the defaults aren’t neutral. They’re engineered. Every platform, every service, every “free” tool exists because someone is making money from your behavior. The path of least resistance has been carefully constructed to serve agendas that aren’t yours.

Your identity, if you’re not careful, gets formed by algorithm rather than intention.

The cost shows up in creative agency. When you spend years in reactive mode, responding to inputs rather than generating outputs, you forget how to initiate. You forget how to create something from nothing. You forget that you can decide what to make, what to think, what to pursue, independent of what the systems around you are suggesting.

I felt this erosion in my own creative practice. After a day of scrolling, the blank page felt impossible. My imagination had been replaced by references. My originality had been crowded out by inputs. I couldn’t hear my own voice through the noise of everyone else’s content.

Drift culture doesn’t kill creativity suddenly. It crowds it out gradually, one scroll session at a time.

And the deepest cost, the one that took me years to recognise, is this: directionless living serves external agendas, not personal evolution.

Every hour you spend drifting is an hour someone else is using to build their outcome. The platforms need your attention to sell ads. The content creators need your engagement to grow their audience. The algorithm needs your data to refine its predictions. Everyone has a plan for your life except you.

The tragedy is that drift feels easier. It feels like rest, like relaxation, like just going with the flow. And compared to the constant pressure of corporate goal-setting, compared to the tyranny of productivity culture, drift can feel like rebellion.

But it’s not rest. It’s just a different form of exhaustion.

And it’s not rebellion. It’s surrender to a different set of masters.

The real cost of directionless living isn’t that you end up nowhere. It’s that you end up somewhere you never chose, serving purposes you never agreed to, wondering how you got here and why the life you’re living doesn’t feel like yours.

Because it isn’t.

It’s the accumulated result of ten thousand unconsidered defaults, each one reasonable in isolation, devastating in aggregate.

Outcome Thinking as Philosophical Practice

Strip away the corporate language, and outcome thinking reveals itself as something far older than quarterly business reviews. It’s a practice of conscious authorship. It’s the choice to write your story deliberately rather than let it be written by default.

But we need to make a critical distinction here, because the term “outcome” has been poisoned by decades of management consultants and productivity gurus. When I say outcome thinking, I’m not talking about SMART goals. I’m not talking about key performance indicators or objective key results or any of that tactical machinery.

Those frameworks treat outcomes as destinations: fixed points you either reach or fail to reach, measured in metrics that someone else probably defined.

That’s not what I’m pointing at.

Outcome thinking, as a philosophical practice, treats outcomes as compass headings, not destinations. It’s the difference between saying “I will be in Madrid on June 15th at 3pm” and saying “I’m heading south.” One is brittle and binary. The other is flexible and directional.

The practice starts with a deceptively simple question: “Where am I actually going?”

Not where you should go. Not where someone else wants you to go. Not where the algorithm is nudging you. Where are you actually going if you keep doing what you’re doing right now?

Most people can’t answer this question because they’ve never asked it. They’re moving, certainly. They’re busy. They’re productive by some measure. But movement isn’t direction. Activity isn’t intention.

I spent years confusing the two.

I’d look at my calendar and see it packed with meetings, commitments, and obligations. I’d look at my to-do list and see tasks getting checked off. I was accomplishing things. But I couldn’t tell you what I was building toward. I was busy going nowhere in particular, which is just drifting with better scheduling.

Outcome thinking forces you to look up from the tactics and ask the strategic question, “What do I want to be true?”

Not what do I want to do. Not what do I want to have. What do I want to be true about my life, my work, my creative practice, and my relationships?

This is where the practice becomes philosophical rather than tactical.

Because answering that question requires you to take a position. It requires you to declare what matters to you, what you value, and what kind of life you’re trying to build. It requires you to distinguish between goals (external metrics, often imposed) and outcomes (states of being, internally generated).

A goal might be “publish a book”. An outcome might be “become someone who writes regularly.” The goal is binary and external. The outcome is continuous and internal.

A goal might be “get promoted to director.” An outcome might be “develop the kind of leadership presence that makes people want to work with me.” The goal is a title. The outcome is a way of being.

You can fail to achieve a goal and still embody the outcome. You can achieve a goal and completely miss the outcome.

The practice of outcome thinking is learning to distinguish between these and choose the one that actually serves your evolution.

This is self-authorship in the truest sense. You’re not just reacting to the story as it unfolds. You’re declaring what kind of story you want to be living in. You’re establishing the genre, the themes, the direction of the narrative arc.

Because here’s what happens when you get clear on your outcome: everything else becomes a filtering mechanism.

Opportunities present themselves constantly. Invitations, offers, requests, suggestions, distractions. In drift mode, you say yes to whatever seems interesting or urgent. In outcome mode, you ask: “Does this move me toward what I want to be true?”

If yes, engage. If no, decline. If unclear, investigate.

This isn’t about rigid plans immune to chaos. Life is too complex, too alive, too full of genuine surprise for that. Outcome thinking doesn’t eliminate flexibility. It enables flexibility by giving you a reference point.

When you know your heading, you can navigate around obstacles. When you’re drifting, every obstacle looks like a sign to change direction, and you end up blown around by every wind.

The practice requires regular review. Not because you’re tracking metrics, but because you’re checking alignment. You sit down and ask: “Am I still heading where I said I wanted to go? Is what I’m doing building what I said I wanted to build? Or have I drifted off course?”

Course correction isn’t failure. It’s navigation.

Course abandonment without conscious choice, though? That’s drift with extra steps.

What outcome thinking ultimately builds is the muscle of agency. The lived experience that you can choose a direction and move toward it. That you’re not just a passenger in your life, buffeted by circumstance and algorithm. That you can declare an intention and organize your energy around it.

This is existential technology. It’s using consciousness deliberately rather than letting it run on autopilot.

And in a culture engineered to keep you reactive, this practice is quietly revolutionary.

Because directed individuals make different choices than drifting populations. They’re harder to manipulate, harder to monetize, harder to keep scrolling.

They know where they’re going.

And they’re not interested in detours that serve someone else’s outcome.

Practical Application: From Drift to Direction

Theory becomes useful when it translates into practice. So let’s talk about how this actually works in the texture of daily life.

The entry point is simpler than most people expect: start with the question “What do I want to be true?”

Not tomorrow. Not in some distant future when conditions are perfect. Right now, in the life you’re actually living, what do you want to be true about how you spend your time, your attention, your creative energy?

I asked myself this question three years ago, and the answer that surfaced surprised me: “I want to be someone who writes every day.”

Not “I want to write a bestselling book.” Not “I want to be a famous author.” Just: I want daily writing to be true about my life.

That clarity changed everything.

Because once you name the outcome, you can start building protocols that align with it. Not rules imposed from outside, but structures you create to support what you’ve already decided matters.

For me, that meant morning pages. It meant treating my blog as sacred practice rather than content marketing. It meant saying no to morning meetings that would colonize my writing time.

This is the difference between goals and outcomes in practice.

A goal would have been “write 50,000 words this quarter.” That’s measurable, time-bound, external. And it would have made writing feel like an obligation, like something I either succeeded or failed at.

The outcome was “be someone who writes daily.” That’s a state of being, internally verified. On days when I wrote three sentences, I still embodied the outcome. On days when I wrote three thousand words, the same outcome. The metric wasn’t word count. It was identity alignment.

Did I show up to the practice today? Yes or no.

This is how outcome thinking filters opportunities.

Someone invites you to a project. Before you say yes by default or no by anxiety, you ask: “Does this move me toward what I want to be true?”

If your outcome is “build deep expertise in a specific domain,” then scattered side projects might be a no, even if they’re interesting.

If your outcome is “create more space for creative experimentation,” then a high-paying corporate gig that consumes sixty hours a week is probably a no, even if it’s prestigious.

If your outcome is “develop genuine friendships rather than just networking connections,” then certain social obligations become clear nos, and certain coffee invitations become clear yeses.

The outcome becomes the decision-making framework.

I use this daily with information consumption. My outcome around learning is “develop integrated understanding rather than accumulate disconnected facts.” So when I’m tempted to read another article, listen to another podcast, or consume another piece of content, I ask: “Does this deepen something I’m already working with, or is it just another input to file away?”

If it deepens, I engage fully. If it’s just more noise, I let it go.

This has radically reduced my consumption and radically increased my integration.

The practice also requires building personal protocols, small repeating structures that make the outcome easier than the drift.

For my writing outcome, the protocol is coffee gets made after I’ve written at least a paragraph. Not a lot of words. Not a masterpiece. Just proof I showed up. The coffee becomes the reward for embodying the outcome, and my brain has learned the pattern.

For my outcome around physical health, “move my body in ways that feel good rather than punish it,” the protocol is: no exercise I dread. If I’m avoiding a workout, that’s data. Find a different movement practice. This has taken me from forcing myself to run (which I hate) to rollerskating multiple times a week (which I love). Same outcome, better protocol.

Protocols aren’t discipline imposed from outside. They’re intelligence about how you actually work, designed to support what you’ve already decided matters.

The critical practice, though, is regular review.

I sit down monthly with my journal and ask three questions:

“What did I say I wanted to be true?” “What is actually true about how I spent my time and attention?” “Where’s the gap, and what needs to adjust?”

Sometimes the gap is in my behaviour. I said I wanted daily writing, but I’ve been skipping mornings. The adjustment is recommitting to the protocol.

Sometimes the gap is in the outcome itself. I said I wanted to build a particular kind of business, but when I’m honest, I don’t actually want that anymore. The adjustment is changing the outcome and rebuilding the protocols.

This is course correction, not course abandonment.

Course abandonment is what happens in drift mode: you stop doing something because it got hard or boring or because the algorithm served up a shinier option. You never consciously chose to change direction. You just… stopped.

Course correction is conscious: you assess, you decide, you adjust. You maintain agency throughout.

The difference might look subtle from the outside, but it feels completely different from the inside.

One is empowering. The other is erosive.

What I’ve discovered through years of this practice is that outcome thinking doesn’t require massive life overhauls. It doesn’t require quitting your job or burning down your calendar or any of that dramatic reinvention theatre.

It requires small, consistent choices in alignment with what you’ve declared matters.

Say no to one thing that doesn’t serve your outcome. Say yes to one thing that does. Review monthly to check if you’re still heading where you said you wanted to go.

Do this for six months, and your life starts to look different. Do this for three years and you become unrecognisable to your former self.

Not because you executed a perfect plan, but because you kept choosing direction over drift, alignment over default, and intention over algorithm.

That’s the practice.

Resistance and Obstacles

Let’s be honest about why most people don’t do this.

Drift feels easier. It feels like rest, like going with the flow, like not being one of those intense people who optimise everything and turn life into a project plan. Drift feels like permission to just be.

And in a culture that glorifies hustle and productivity theatre, that permission feels like medicine.

But here’s the uncomfortable truth I’ve had to face in my own practice: drift isn’t actually easier. It just frontloads the relief and backloads the cost.

Choosing what to watch on Netflix feels harder than letting it auto-play. Deciding what you want your career to build toward feels harder than just taking the next logical step. Sitting down to write feels harder than scrolling through social media.

In the moment, drift wins on effort.

But zoom out six months, a year, or five years, and the cumulative cost of drift is staggering. The vague dissatisfaction. The sense that time is passing but nothing is building. The creeping feeling that you’re living someone else’s life. The exhaustion that comes from constant input without meaningful output.

That’s not easier. That’s just delayed difficulty.

Outcome thinking frontloads the difficulty and backloads the relief. The hard part is upfront: deciding what you want, facing the discomfort of choice, and taking responsibility for direction. But once you’ve done that work, the daily decisions get simpler. You have a framework. You know what you’re building toward.

Still, the resistance is real.

There’s enormous cultural pressure toward “going with the flow.” It shows up in spiritual bypassing disguised as wisdom. “Don’t be attached to outcomes.” “Let the universe decide.” “Trust the process.” All of which sound enlightened but can easily become justifications for not choosing anything.

I’ve used these phrases myself to avoid the discomfort of declaring what I actually want.

Because here’s what nobody tells you about choosing outcomes: it’s vulnerable.

When you name what you want to be true, you’re putting a stake in the ground. You’re saying “this matters to me” in a world that’s very good at mocking what people care about. You’re creating the possibility of not achieving it, which means creating the possibility of failure.

Drift protects you from that. If you never declare a direction, you can never be lost. If you never say what you’re building, you can never fail to build it.

The ego loves this safety.

But safety isn’t the same as satisfaction. And protection from failure is also protection from meaning.

The fear of choosing “wrong” outcomes is particularly paralysing for people who’ve been trained in optimisation thinking. They want to run the analysis, weigh all options, and find the provably correct path before committing.

But life isn’t a spreadsheet. There is no objectively correct outcome. There’s only what’s true for you, right now, given who you are and what you value.

And that changes. I’ve changed my primary outcome three times in the last decade. Each shift felt like failure until I recognised each outcome built the capacity for the next one.

Another obstacle: the ego’s attachment to being busy versus being directed.

Our culture has a bizarre relationship with busyness. We wear it as a badge of honour. “I’m so busy” becomes a status symbol, proof that you’re important, needed, and in demand.

Outcome thinking threatens this identity.

Because when you get clear on your actual direction, a lot of your busyness reveals itself as distraction. The meetings that don’t serve anything you care about. The projects you said yes to out of obligation. The commitments you’re maintaining because you started them once, not because they’re building anything meaningful.

Letting those go feels like diminishment. It feels like becoming less productive, less valuable, and less impressive.

But what you’re actually becoming is more focused. More intentional. More aligned.

It just doesn’t look as busy from the outside.

I’ve lost friends over this. People who bonded with me over our shared exhaustion, our packed calendars, our heroic tales of juggling too many things. When I started saying no, started protecting my time, started choosing direction over drift, some relationships couldn’t survive the shift.

They needed me to stay in busy mode to validate their own choices.

And maybe the deepest resistance of all: outcome thinking requires you to take responsibility for your life.

Not blame yourself for past drift. Not berate yourself for unconsidered defaults. But accept that from this moment forward, you’re choosing. And if you don’t like where you’re going, you have the power to choose differently.

That power is simultaneously liberating and terrifying.

Because once you know you can choose, you can’t un-know it. You can’t go back to comfortable drift and pretend you had no agency. Every time you’re scrolling mindlessly, some part of you knows you chose that. Every time you say yes to something that doesn’t serve your outcome, you’re conscious of the betrayal.

This awareness can feel like a burden.

But it’s actually the price of authorship.

If you want to write your own story, you have to accept that you’re writing it. Every scene. Every chapter. Every choice that compounds into the narrative arc of your life.

You can’t blame the algorithm anymore. You can’t blame circumstances. You can’t blame drift.

You’re the one holding the pen.

And that responsibility, uncomfortable as it is, turns out to be the foundation of something worth having: a life that actually feels like yours.

Final thoughts

Here’s the choice that presents itself every single day, whether you’re conscious of it or not: author or character.

Author: someone who knows the story they’re writing, even if they don’t know how every scene will unfold. Someone who chooses the themes, sets the direction, and decides what kind of narrative they’re building.

Character: someone being moved through a story written by algorithm, by default, by cultural momentum, or by whoever has the strongest claim on their attention that day.

Both are roles in the same life. But they feel completely different from the inside.

I’ve lived both. Years as a character, accepting whatever plot points showed up, reacting to the story as it happened to me. Then a gradual, sometimes painful transition into authorship. Learning that I could choose. That choosing was even possible. That the pen was in my hand the whole time; I’d just been letting others move it.

The transition isn’t a one-time decision. It’s a daily practice.

Because drift doesn’t disappear just because you’ve decided to steer. The currents are still there. The algorithms are still optimised. The defaults still pull. The path of least resistance still slopes downward into passive consumption.

Outcome thinking as a practice means recommitting to authorship every morning.

It’s not dramatic. It’s not a transformation montage with inspiring music. It’s quieter than that. More persistent. More mundane.

But the compounding effect is staggering.

Six months of writing daily instead of scrolling daily: you’ve built a body of work.

A year of saying no to obligations that don’t serve your outcome: you’ve reclaimed hundreds of hours for what actually matters.

Three years of filtering opportunities through your declared direction: you’ve become someone different. Not because you executed a perfect plan, but because you kept choosing alignment over drift, intention over default.

That’s how you build a life that feels like yours.

Not perfect. Not immune to chaos or surprise or necessary pivots. But yours. Authored. Chosen. Directed.

And here’s what becomes possible when you stop drifting and start steering:

You stop waiting for permission and start creating what wants to exist through you.

You stop consuming other people’s stories and start telling your own.

You stop being optimised by systems that profit from your distraction and start optimising yourself toward your own declared outcomes.

You stop being a data point and become a person again. A consciousness with agency. A creator with direction.

The practice is simple. Ancient, actually. Just dressed in a new language for a new context.

Choose what you want to be true. Build small protocols that support it. Review regularly to check alignment. Adjust as needed. Repeat until your life reflects your choices instead of your defaults.

That’s it. That’s the whole practice.

Simple, but not easy. Because it requires you to accept something uncomfortable: you’re responsible for the story you’re living.

Not responsible for everything that happens to you. That’s not how life works. Chaos is real. Circumstances exist. Systems have power.

But responsible for how you respond. For what you choose to build. For where you point your attention and energy. For whether you’re drifting or steering.

That responsibility is the price of authorship.

And authorship is the price of a life that means something.

Not to the algorithm. Not to the engagement metrics. Not to whoever’s trying to monetise your attention this week.

To you.

A life that, when you look back on it, feels like you were actually there. Conscious. Choosing. Building toward something that mattered.

Not drifting through someone else’s story.

Writing your own.

The pen is in your hand.

What are you going to make true?